'Wired' Underwater Volcano May Be Erupting Off Oregon

An underwater volcano off the coast of Oregon has risen from its slumber and may be spewing out lava about a mile beneath the sea.

Researchers were alerted to the possible submarine eruption of the Axial Seamount, located about 300 miles (480 kilometers) off the West Coast, by large changes in the seafloor elevation and an increase in the number of tiny earthquakes on April 24.

Geologists Bill Chadwick, of the Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory and Oregon State University, and Scott Nooner, of the University of North Carolina, Wilmington, successfully forecast the eruption in a blog post in September 2014, though they had presented their ideas at a meeting before then. [Axial Seamount: Images of an Erupting Undersea Volcano]

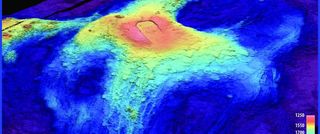

Axial Seamount is an underwater mountain that juts up 3,000 feet (900 meters) from the ocean floor, and is part of a string of volcanoes that straddle the Juan de Fuca Ridge, a tectonic-plate boundary where the seafloor is spreading apart.

Chadwick and Nooner have been monitoring the seamount for the past 15 years by measuring tiny movements in the seafloor as the volcano inflates with magma and then deflates. During that period, the volcano has erupted two other times — once in 1998 and again in 2011.

"It's kind of like a balloon — as magma is going into the balloon, it's inflating, and it pushes the seafloor up," Chadwick told Live Science. "As more and more magma gets in, the pressure builds. Eventually, it reaches some critical pressure where [the seamount] can't hold it in anymore, and then it squirts out."

After the volcano erupts, the seafloor drops very rapidly, "like letting air out of a balloon," he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

World's first 'wired volcano'

For the first time, Chadwick and his colleagues were able to observe the eruption in real time, thanks to a set of instruments connected to shore by a fiber-optic cable, installed last summer by the University of Washington and paid for by the National Science Foundation.

"This is the first place in the world where we have a wired volcano on the seafloor," Chadwick said.

Last week, the center of the volcanic crater dropped by about 6.5 feet (2 m) over a period of 12 hours, and the number of tiny earthquakes increased from hundreds per day to thousands per day, Chadwick said. On April 24, there were 8,000 earthquakes in one day, he said. (The earthquakes are too small to cause any harm to coastal residents or to trigger a tsunami, the researchers noted.)

The measurements came from eight seismometers installed around the edge of the Axial Seamount's large caldera, as well as sensors that measure changes in water pressure as the volcano's surface inflates or deflates.

"If the seafloor is going up, there's less ocean above you, so there's a little less pressure," Chadwick said. "It's not much, but our instruments are so sensitive [that] we can measure to within a millimeter of vertical motion."

Ongoing rumblings

The seamount last erupted in April 2011. Scientists discovered the eruption by accident, on a routine expedition to the seamount in late July. They were planning to retrieve some instruments they had left there the year before, when a robotic vehicle sent down to explore the site revealed a fresh lava flow that was more than 12 feet (4 m) thick in places.

Nooner and Chadwick have been monitoring the Axial Seamount since its previous eruption in 1998. Back in 2006, they forecast the seamount was due for another eruption again before 2014, which then occurred in 2011.

Chadwick and Nooner plan to return to the seamount this summer by ship, to confirm that an eruption occurred (Nooner said it would probably finish erupting before then), and to retrieve data stored on instruments that aren't connected to the cable observatory.

"The goal is to understand the basic behavior of volcanoes, because we really don't understand how magma chambers work and how magma works its way up through the crust," Nooner told Live Science.

In addition to the volcano, the site is home to hydrothermal vents and an entire biological ecosystem, which many different scientists are studying.

Editor's Note: This article was updated at 7:51 p.m. ET May 2, to correct the distance the crater center dropped in a 12-hour period, and to clarify an earlier eruption prediction.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.