Spleen: Function, Location & Problems

It is possible to live without it, but removal of the spleen has serious consequences.

The spleen is the largest organ in the lymphatic system. It is an important organ for keeping bodily fluids balanced, but it is possible to live without it, according to Mayo Clinic.

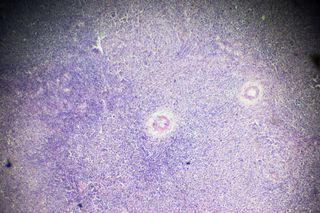

The spleen is located under the ribcage and above the stomach in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen. A spleen is soft and generally looks reddish purple, according to StatPearls, a database of medical reference articles. It is made up of two different types of tissue. According to Britannica, the red pulp tissue filters the blood and gets rid of old or damaged red blood cells. The white pulp tissue consists of immune cells (T cells and B cells) and helps the immune system fight infection.

What size is it?

According to Medical News Today, a helpful tip to remember the size of the spleen is the 1x3x5x7x9x11 rule:

- An adult spleen measures around 1 inch by 3 inches by 5 inches.

- It weighs around 7 oz.

- It is located between the 9th and 11th ribs.

Main function

"The spleen acts as a blood filter; it controls the amount of red blood cells and blood storage in the body, and helps to fight infection," said Jordan Knowlton, an advanced registered nurse practitioner at the University of Florida Health Shands Hospital. If the spleen detects potentially dangerous bacteria, viruses, or other microorganisms in the blood, it — along with the lymph nodes — creates white blood cells called lymphocytes, which act as defenders against invaders, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine. The lymphocytes produce antibodies to kill the foreign microorganisms and stop infections from spreading.

According to the Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC, when blood flows into the spleen, red blood cells must pass through narrow passages within the organ. Healthy blood cells can easily pass, but old or damaged red blood cells are broken down by large white blood cells. The spleen will save any useful components from the old blood cells, including iron, so they can be reused in new cells. The blood vessels in the spleen can expand in order to store blood, UPMC reported. They widen or narrow, depending on the body's needs. This allows the spleen can hold up to a cup of reserve blood.

Spleen problems

Lacerated spleen or ruptured spleen

According to Knowlton, spleen lacerations or ruptures "usually occur from trauma (like a car accident or contact sports)." These emergency situations cause a break in the spleen's surface and can lead to "severe internal bleeding and signs of shock (fast heart rate, dizziness, pale skin, fatigue)," said Knowlton. The Mayo Clinic reported that without emergency care, the internal bleeding could become life-threatening.

On the continuum of spleen breakage, a laceration refers to a lower-grade extent of injury, in which just a part of the spleen is damaged. A ruptured spleen is the highest grade of broken spleen injury, according to HealthTap, an online network of doctors who answer health questions.

According to Medical News Today, symptoms of a lacerated or ruptured spleen include pain or tenderness to the touch in the upper left part of the abdomen, left shoulder and left chest wall, as well as confusion and lightheadedness. If you experience any of the symptoms after a trauma, seek emergency medical attention immediately.

Treatment options depend on the condition of the injury, according to the Mayo Clinic. Lower-grade lacerations may be able to heal without surgery, though they will probably require hospital stays while doctors observe your condition. Higher-grade lacerations or ruptures may require surgery to repair the spleen, surgery to remove part of the spleen, or surgery to remove the spleen completely.

Humans can live without their spleen, but those without one may be more susceptible to infection.

Related: What Organs Can You Live Without?

Enlarged spleen

An enlarged spleen, also called a splenomegaly, is a serious but typically treatable condition. "An enlarged spleen puts one at risk for rupture," said Knowlton. According to the Mayo Clinic, anyone can get an enlarged spleen, but children suffering from mononucleosis, adults with certain inherited metabolic disorders including Gaucher's and Neimann-Pick disease, and people who live or travel to malaria-endemic areas are more at risk.

Knowlton listed infection, liver diseases, cancer, and blood diseases as typical causes for enlarged spleens. According to the Mayo Clinic, specific infections and diseases include:

- viral infections, such as mononucleosis

- bacterial infections

- parasitic infections, such as malaria

- metabolic disorders

- hemolytic anemia

- liver diseases, such as cirrhosis

- blood cancers and lymphomas, such as Hodgkin's disease

- pressure on or blood clots in the veins of the liver or spleen

In many cases, there are no symptoms associated with an enlarged spleen, according to NHS inform. Doctors typically discover the condition during routine physicals because they can feel enlarged spleens. When there are symptoms, they might include:

- pain in the upper left abdomen that may spread to the shoulder

- fatigue

- anemia

- bleeding easily

- feeling full without eating

Typically, enlarged spleens are treated by addressing the underlying problem, according to the Mayo Clinic. If the cause of the enlarged spleen can't be determined or if the condition is causing serious complications such as a ruptured spleen, doctors may suggest removing the spleen.

Spleen cancer

Cancers that originate in the spleen are relatively rare. When they do occur, they are almost always lymphomas, blood cancers that occur in the lymphatic system. Usually lymphomas start in other areas and invade the spleen. According to the National Cancer Institute, adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma can have a spleen stage. This type of spleen invasion can also happen with leukemia, blood cancer that originates in bone marrow. Rarely, other types of cancers — like lung or stomach cancers — will invade the spleen, according to the Journal of Clinical and Experimental Pathology.

Spleen cancer symptoms may resemble a cold or there may be pain or fullness in the upper abdomen, according to Medical News Today. An enlarged spleen can also be the result of spleen cancer.

Treatment for spleen cancer will depend on the type of cancer and how much it has spread. The National Cancer Institute lists spleen removal as a possible treatment.

Spleen removal

Spleen removal surgery is called a splenectomy. Knowlton said that the procedure is done in cases such as: "trauma, blood disorders (idiopathic thrombocytopenia purpura (ITP), thalassemia, hemolytic anemia, sickle cell anemia), cancer (lymphoma, Hodgkin disease, leukemia), and hypersplenism to name a few."

Spleen removal is typically a minimally invasive laparoscopic surgery, according to the Cleveland Clinic, meaning that surgeons make several small incisions and use special surgical tools and a small camera to conduct the surgery. In certain cases, a surgeon may opt for one large incision, instead.

"You can live without a spleen because other organs, such as the liver and lymph nodes, can take over the duties of the spleen," said Knowlton. Nevertheless, removing the spleen can have serious consequences. "You will be more at risk to develop infections," said Knowlton. Often, doctors recommend getting vaccines, including a pneumococcus vaccine, Haemophilus B vaccine, Meningococcal vaccine, and yearly flu vaccine after a splenectomy, according to University of Michican Hospitals and Health Centers. It is important to see a doctor at the first sign of infection if you do not have a spleen.

This article is for informational purposes only, and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Additional reporting by Alina Bradford, Live Science contributor.

This article was updated on Sept. 16, 2021 by How It Works staff writer Ailsa Harvey.

Editor's Note: If you’d like more information on this topic, we recommend the following book:

Additional Resources

- Take a closer look at the spleen at Encyclopedia Britannica

- Read more about spleen diseases: U.S. National Library of Medicine

- Overview of the Spleen: Merck Manual

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Jessie Szalay is a contributing writer to FSR Magazine. Prior to writing for Live Science, she was an editor at Living Social. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from George Mason University and a bachelor's degree in sociology from Kenyon College.