What If We Eradicated All Infectious Disease?

In this weekly series, Life's Little Mysteries provides expert answers to challenging questions.

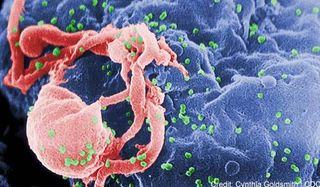

Imagine a world with no HIV, no malaria, no tuberculosis, no flu and so on down to the absence of the common cold. With scientists chasing after cure-all anti-virus treatments and a universal flu vaccine in labs around the world, the eradication of infectious diseases certainly appears to be medical research's ultimate (if remote) goal. But what if we actually got there?

As the Princeton mathematical epidemiologist Nim Arinaminpathy put it, "If we had a magic pill that got rid of all infectious diseases, period, would we really use it?" He isn't sure. In all likelihood, purging humanity of infectious disease would not be a universally positive eventuality, but it wouldn't trigger the immediate downfall of Homo sapiens, either.

Survival of the unfittest

First, consider what we'd be giving up. "Our evolutionary history has been a continual arms race against the pathogens that plague us," said Vincent Racaniello, professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University. For eons, this battle has weeded out the weak, and in a less combative environment, standards for human survival would grow lax.

However, this is not quite as problematic as it might seem. In much of the West, "people are already kind of artificial animals," Racaniello told Life's Little Mysteries. "We have all these ways of intervening when people get sick, when otherwise they would have died and we would see some natural selection for people with more robust immune systems." But as long as doctors keep having a way to render moot those diseases that used to kill us, natural immunity isn't essential, he said.

And in fact, many diseases could be eradicated worldwide without any loss of evolutionary robustness. "With influenza, there isn't any indication that this plays a role in human evolution," said Arinaminpathy, who studies the evolutionary effects of flu vaccines. A pathogen can only impact human DNA if it tends to kill people before they have offspring. Otherwise, its victims have already passed on their genes to the next generation, regardless of whether those genes made them susceptible to the pathogen or not. The flu is most fatal to the elderly, who have typically already passed on their genes. [How Many Genetic Mutations Do I Have?]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Meanwhile, malaria does target the young, and it therefore molds the evolution of people in many tropical countries by killing children with feeble immune defenses (leaving behind those with malaria-resistant genes). But this "survival of the fittest" situation is not desirable; malaria has been largely eradicated in the United States with no obvious downsides. If the same were to happen in Africa and other afflicted regions, "the impact of reducing or removing malaria would go beyond public health," Arinaminpathy said.

A healthy population

The malaria parasite is so rampant in Africa that many children are afflicted over and over in a nearly continuous cycle. "You can't think clearly, you feel terrible, and it stops you from being able to go to school or have a productive life," Racaniello said. Meanwhile, HIV is running amok in sub-Saharan Africa, similarly stifling development and productivity. ['Superdrug' Could Fight Both HIV and Malaria]

In short, disease ushers in poverty. "If you get rid of infectious diseases by vaccination," Racaniello said, "you can make a big contribution to getting people out of poverty so they can have productive lives."

And although wiping out malaria, tuberculosis, sleeping sickness, HIV and the other tropical plagues would mean significant population growth in just the areas that are already experiencing runaway birth rates and food crises, these socioeconomic problems would be far more tractable in a disease-free society. "If a good fraction of these individuals have productive careers they might come up with solutions," he said.

These considerations all suggest eradicating infectious diseases would benefit humanity, on balance. But there's one giant question left.

Good colds?

Does regularly getting the cold or the flu when we're young help us later? These viruses might somehow aid in the growth and development of our metabolisms, or even our organs. Scientists aren't sure, because they haven't had the chance to study a virus-free human population, as they have with the bacteria- and parasite-lacking populations in the West.

"We're just learning that the consequence of antibiotics is that when you get rid of the good bacteria in our guts, we can develop autoimmune diseases [such as allergies]. We're not as advanced in our understanding of viruses. What do viruses do for us?" Racaniello said.

Allergies we can live with, but some of the benign viruses that hitch a ride in our bodies could be serving a much deeper role, Arinaminpathy said — as could a few of the slightly virulent ones with whom our relationship is "a bit fuzzy." Would a world in which babies were permanently inoculated against the cold, the flu, HPV and everything else actually be better?

Like always, we should we careful what we wish for. Ridding the world of diseases would be "mostly a good thing," Arinaminpathy said, "but there are these interesting questions when you scratch the surface of these illnesses."

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.