Who invented the bicycle?

The bicycle has a complicated past fraught with controversy and misinformation.

You might think that an invention as simple as the bicycle would have an uncomplicated past. But as it turns out, this highly popular invention has a history fraught with controversy and misinformation. While stories about who invented the bicycle often contradict one another, there's one thing that's certain: the very first bicycles were nothing like the ones you see cruising down the street today.

The first known iterations of a wheeled, human-powered vehicle were created long before the bicycle became a practical form of transportation. In 1418, an Italian engineer, Giovanni Fontana (or de la Fontana), constructed a human-powered device consisting of four wheels and a loop of rope connected by gears, according to the International Bicycle Fund (IBF).

In 1813, about 400 years after Fontana built his wheeled contraption, a German aristocrat and inventor named Karl von Drais began work on his own version of a Laufmaschine (running machine), a four-wheeled, human-powered vehicle. Then in 1817, Drais debuted a two-wheeled vehicle, known by many names throughout Europe, including Draisienne, dandy horse and hobby horse, IBF says.

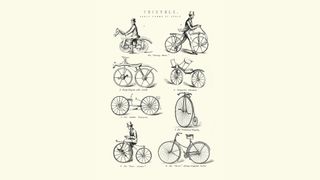

Curious contraptions

Drais built his machine in response to a very serious problem: a dearth of real horses. In 1815, Indonesia's Mount Tambora erupted and the ash cloud that dispersed around the world lowered global temperatures. Crops failed, and many animals, including horses, died of starvation, according to Smithsonian Magazine.

Drais' hobby horses were a far cry from the aerodynamic speed machines that are today's bicycles. Weighing in at 50 pounds (23 kilograms), this bicycle ancestor featured two wooden wheels attached to a wooden frame. Riders sat on an upholstered leather saddle nailed to the frame and steered the vehicle with a rudimentary set of wooden handlebars. There were no gears and no pedals, as riders simply pushed the device forward with their feet.

Drais took his invention to France and to England, where it became popular. A British coach maker named Denis Johnson marketed his own version, called "pedestrian curricles," to London's pleasure-seeking aristocrats. Hobby horses enjoyed several years of success before they were banned from sidewalks as a danger to pedestrians. The fad passed, and by the 1820s, the vehicles were rarely seen, according to the National Museum of American History (NMAH).

Bone shakers and penny-farthings

Bicycles made a comeback in the early 1860s with the introduction of a wooden contraption with two steel wheels, pedals and a fixed gear system. Known as a velocipede (fast foot) or a "bone shaker," the brave users of this early contraption were in for a bumpy ride.

The question of who invented the velocipede, with its revolutionary pedals and gear system, is a bit murky. A German man named Karl Kech claimed that he was the first to attach pedals to a hobby horse in 1862. But the first patent for such a device was granted not to Kech but to Pierre Lallement, a French carriage-maker who obtained a U.S. patent for a two-wheeled vehicle with crank pedals in 1866, according to the NMAH.

In 1864, before securing his vehicle's patent, Lallement exhibited his creation publicly, which may explain how Aime and Rene Olivier — two sons of a wealthy Parisian industrialist — learned of his invention and decided to create a velocipede of their own. Together with a classmate, Georges de la Bouglise, the young men enlisted Pierre Michaux, a blacksmith and carriage maker, to create the parts they needed for their invention.

Michaux and the Olivier brothers began marketing their velocipede with pedals in 1867, and the device was a hit. Because of disagreements over design and financial matters, the company that Michaux and the Oliviers founded together eventually dissolved, but the Olivier-owned Compagnie Parisienne lived on.

By 1870, cyclists were fed up with the lumbering bone-shaker design popularized by Michaux, and manufacturers responded with new designs. Also by 1870, metallurgy had advanced enough that bicycle frames could be made of metal, which was stronger and lighter than wood, according to the IBF.

One popular design was the high wheeler, also known as the penny farthing because of the size of the wheels. (A farthing was a British coin that was worth one-fourth of a penny.) A penny farthing featured a smoother rise than its predecessor, due to its solid rubber tires and long spokes. Front wheels became larger and larger as manufacturers realized that the larger the wheel, the farther one could travel with one rotation of the pedals. A riding enthusiast could get a wheel as large as their legs were long.

Unfortunately, the large front-wheel design championed by thrill-seeking young men — many of whom took to racing these contraptions at newly founded bicycle clubs across Europe — was not practical for most riders. If the rider needed to stop suddenly, momentum carried the entire contraption over the front wheel and landed the rider on his head. This is where the term "taking a header" came into being, according to the IBF. Enthusiasm for penny-farthings remained tepid until an English inventor named John Kemp Starley came up with a winning idea for a "safety bicycle" in the 1870s.

Starley began successfully marketing his bicycles in 1871, when he introduced the "Ariel" bicycle in Britain, kicking off that nation's role as the leader in bicycle innovation for many decades to come.

Starley is perhaps best known for his invention of the tangent-spoke wheel in 1874. This tension-absorbing front wheel was a vast improvement over the wheels found on earlier bicycles and helped make bike riding a (somewhat) comfortable, enjoyable activity for the first time in history. Starley's wheels also made for a much lighter bike, another practical improvement over previous iterations.

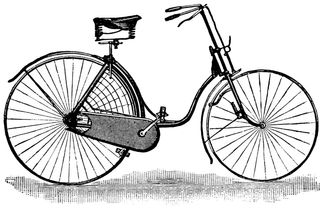

Then, in 1885, Starley introduced the "Rover." With its nearly equal-sized wheels, center pivot steering and differential gears that operated with a chain drive, Starley's "Rover" was extremely stable, and the first highly practical iteration of the bicycle.

The number of bicycles in use boomed from an estimated 200,000 in 1889 to 1 million in 1899, according to the NMAH.

At first, bicycles were a relatively expensive hobby, but mass production made the bicycle a practical investment for the working man, who could then ride to his job and back home. The bicycle introduced thousands to individual and independent transportation, and provided greater flexibility in leisure. As women started riding in great numbers, dramatic changes in ladies' fashion were required. Bustles and corsets were out; bloomers were in, as they gave a woman more mobility while allowing her to keep her legs covered with long skirts.

Bicycles were also partly responsible for better road conditions. As more Americans began to ride bicycles, which needed a smoother road surface than a horse-drawn vehicle, bicyclists organized to demand better roads, according to the NMAH. They were often joined by railroad companies that wanted to improve the connections between farmers and other businesses and the rail station.

The bicycle had a direct influence on the introduction of the automobile, according to the NMAH. Bicycle parts were later incorporated into automobile parts, including ball bearings, differential units, steel tubing and pneumatic tires.

Many pioneer automobile builders were first bicycle manufacturers, including Charles Duryea, Alexander Winton and Albert A. Pope. Also, Wilbur and Orville Wright were bicycle makers before turning their attention to aerodynamics. Glenn Curtiss, another aviation pioneer, also started out as a bicycle manufacturer.

As automobiles rose in popularity, though, interest in bicycles waned. Also, electric railways took over the side paths originally constructed for bicycle use, according to the NMAH. The number of manufacturers shrank in the early 1900s, and for more than 50 years, the bicycle was used largely only by children.

A reawakening of adult interest occurred during the late 1960s as many people began to see cycling as a non-polluting, non-congesting means of transportation and recreation. In 1970, nearly 5 million bicycles were manufactured in the United States, and an estimated 75 million riders shared 50 million bicycles, making cycling the nation's leading outdoor recreation, according to the NMAH.

Bicycles today

Over 100 million bicycles are manufactured each year, according to the website Bicycle History, and an estimated 1 billion bicycles are currently being used all around the world.

A person walking into a bicycle store today is faced with a wide range of options. Frames are designed and made from different materials based on where the bicycle might be ridden. They might be crafted from steel, aluminum, titanium, or carbon fiber, or occasionally even out of materials such as bamboo, according to Bike Bamboo. Wheels come in a variety of sizes and thicknesses for rolling over various surfaces: from rough, dirt-covered and rocky mountain roads to smooth, paved city streets. Riders can choose between different types of brakes, gear numbers, seat shapes, handlebar positions and bends, and whether or not to have suspension.

Bicycles can have anywhere from one to 33 gears. Seats may be short and narrow for racing, or wide and cushioned seats for comfortable rides. Suspension can be added to give a smoother ride on bumpy paths.

And some modern bicycle designs differ so greatly from their predecessors that they would probably be unrecognizable as bicycles to early inventors. Today, bicycles can fold up to make traveling or storage easier. Some have no seats and resemble elliptical machines that you might find at the gym; other bikes have attached strollers for cycling with young children, and some even come with electric motors.

Additional resources

Trace the evolution of the bicycle through photographs, in a slideshow at the Bicycle Museum of America's website. Learn more from Reliance Foundry about how bike infrastructure can reduce the risk of serious injuries and fatalities to cyclists, and discover the pros and cons of bike-riding in an international study of more than 1,000 cyclists in 20 countries, published in 2019 in the journal Transportation Research.

Additional reporting by Rachel Ross, Live Science contributor, and Tim Sharp, Reference editor. This article was updated on Feb. 25, 2022 by Live Science senior writer Mindy Weisberger.

Bibliography

"Bicycle History (& Human Powered Vehicle History)." Bicycle History Timeline, http://www.ibike.org/library/history-timeline.htm.

Magazine, Smithsonian. "Blast from the Past." Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution, 1 July 2002, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/blast-from-the-past-65102374/.

"America on the Move." National Museum of American History, 3 July 2019, http://amhistory.si.edu/onthemove/themes/story_69_2.html.

"Bicycle History - Story of Two-Wheelers for Transportation." Bicycle History - Evolution of Cycling, http://www.bicyclehistory.net/.

"Bicycle History." THE BICYCLE MUSEUM OF AMERICA, http://www.bicyclemuseum.com/bicycle-history/.

"Essential Guide to Bike Infrastructure." Reliance Foundry Co. Ltd, 17 Jan. 2022, https://www.reliance-foundry.com/blog/bikeways-bike-infrastructure.

Useche, Sergio A., et al. "Healthy but Risky: A Descriptive Study on Cyclists' Encouraging and Discouraging Factors for Using Bicycles, Habits and Safety Outcomes." Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, Pergamon, 4 Mar. 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1369847818306934.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Elizabeth is a former Live Science associate editor and current director of audience development at the Chamber of Commerce. She graduated with a bachelor of arts degree from George Washington University. Elizabeth has traveled throughout the Americas, studying political systems and indigenous cultures and teaching English to students of all ages.